First Week

Hello!

Entering France

I had two layovers, one in Atlanta and another in Paris. To board both flights, I had to show a copy of my vaccination card and passport. However, I did not realize that immigration checks take place in the first city in a new country, even if connecting through. So, with my 75 minute connection at CDG airport, I barely had enough time to make it through security and passport check. At CDG security, I got pulled aside for having 4-inch long scissors that I forgot to put in my checked bag, oops. Surprisingly these did not get confiscated by US security. As a result of this, my bag and shoes also got swabbed for explosive testing. After making it through, I was surprised that there were no additional customs to go through once I landed in Toulouse. I did not get a passport stamp or need to show any proof of how long I was staying, sufficient funds, or a return flight (though I had booked a refundable flight to Iceland in case).

Settling in

I landed in Toulouse in the afternoon and took a local bus to my studio. Check-in at the Airbnb was a breeze. After dropping off my bags, I took a walk around City Centre, which is completely decked out for the holidays. String lights line almost every offshoot from the Capitole, all the way to the Garonne river. The Capitole itself is set up for the Marché de Noël, which is a Christmas market similar to Bryant Park during the Holidays. They require the Pass Sanitaire, which is a QR code required for most indoor or crowded public spaces in France. Non-EU nationals can apply for this at pharmacies with a physical vaccination card. While near Capitole, I stopped at the post office to buy international stamps (to my family: check your mail soon)!

On my walk back, I stopped at an ATM to pick up some Euros to have on hand. This was a better exchange rate than if I had ordered currency from a bank in the US. I also stopped at Monop, a supermarket, to pick up some essentials and scope out the yogurt section. I also must say I have never seen a jar of nutella (10.50 Euros per kg) selling for cheaper than a jar of peanut butter (15.44 Euros per kg). What’s a girl to do, bring nutella and jelly sandwiches to lab?

Here I should probably mention I don’t speak much French. I can understand more than I can speak. Even so, hearing the language spoken in an audio exercise from a textbook is very different than standing in line at a market, with five people behind you, puzzled about whether the cashier is asking you if you need a receipt or a bag. I think Merci, Pardon, and Ça va have been doing some good work for me, but I hope my time here will expand my knowledge of the language.

Meeting the Lab

I spent a day recovering, but I had gotten over jet lag quickly (or so I thought). On Thursday, I woke up and headed down to Jean-Jaurès metro station, which is just across the street from my studio. It was going to be a 20 minute ride and 7 minute walk to lab, but I left an hour early because I was excited to explore and meet the group. On my way to the metro station, I stopped at La Mie de Pain, and got a chocolate croissant (for only one Euro!). I stashed the croissant for my walk, and entered the metro station. There were self-service kiosks but I was bold and wanted to test out my French, so I walked into the Tisséo office. Through the mask and plastic barrier, I could barely hear the agent and think I asked her to “pouvez-vous répéter” at least seven times. For one month of unlimited public transport at my age, the cost was 8 Euros for the Pastel card and 16 Euros for the transit itself. For verified French students, transit is free! Amazing.

The metro cars were understandably busy for a weekday morning, but the bulk of the passengers (including me) disembarked at the University’s three stops. I found the Centre de Biologie Intégrative after enjoying a stroll through campus enjoying my croissant. I met up with Prof. Jean-Yves Bouet, co-lead of the Genome Dynamics (GeDy) team, who showed me around his lab. There are ample GeDy / Jedi posters showing the team merged onto Star Wars scenes, and the space is quite nice.

Researchers at CBI are appointed through the CNRS, or France’s state science agency. It is Europe’s largest fundamental science agency. I found Prof. Bouet through CBI’s website, where his research in bacterial chromosome organization and plasmid segregation piqued my interest. After chatting with him on zoom in November, he shared that he is an avid kefir fermenter (I’ll be sampling this next week!) The other researchers in the group were all very welcoming, and, while I tried to avoid this feeling, it was comforting to speak English with someone for the first time in a few days.

I chatted with Prof. Bouet about French PhD programs. During the conversation, he mentioned he did his PhD there, in the very building he now leads a group in. Usually French PhD programs are three years, with no rotations, and projects are assigned upon admission. We discussed how, while the expedited time frame can be beneficial, it runs the risk of not giving enough time for a student to fully develop different aspects of a project. Lengthier US PhD programs give students time to develop ideas and, well, fail more. Failure is a part of science and running into roadblocks early on can help scientists learn how to overcome challenges. Especially during COVID, Prof. Bouet says, it was hard for students to get enough lab time to finish within their funding timeline. Having a sharp deadline to graduate during a pandemic posed definite challenges.

We spent some time marvelling about how sequencing is so prevalent that many young researchers (myself included) sometimes do not take the time to revel in the wonder of it. We can ship DNA in the mail. The next day, we can see letters on our screen. Prof. Bouet shared his experience sequencing one of the key genes in T4. He worked his way in from the ends of the 3.5 kb segment. After every PCR, he had to order new primers just to keep being able to PCR inward. For something that would take less than 24 hours today, Prof. Bouet had to spend three months on it. And that was quick for the time, because the University had in-house oligo synthesis. Stories like these put the techniques we have today into perspective. Me, and other scientists around my age, will not know the burden of trying to hack our way through PCR sequencing or compiling our code by hand. But then again, professors today do not know the burden of mouth pipetting (I hope).

Later that day, there was a seminar hosted by a researcher retiring from CBI. I meant to go on Zoom – the talks sounded interesting – but when I got home, I fell asleep for a while. And thus began the vicious cycle of sleeping from 4-6 PM, 11 PM-1 AM, and 7 AM - 11 AM. I might have finally kicked that schedule, but I will have to see it to believe it.

Getting The Project Moving Again

I spent the next two days exhausted from the strange sleep schedule, and started to feel guilty for just being at home. It feels surreal to be in a new city, alone, with so much to see and explore, but all I could do was read, watch Netflix (which still has Friends in France!), and go for walks along the river. Dusk at the Garonne River has been one of the most serene times for me to reflect. Here’s something I wrote Friday night after reading the (very interesting) plaques along the river.

“I sit on the bank of the Garonne. To my left is the Pont-Neuf, or new bridge, named so because it is relatively new, built in the 16th century. I am looking ahead at the Hôtel-Dieu Saint-Jacques, a lovely pair of buildings from 1257. They look like some ancient fortress ready to receive ships along the water, but instead they are hospital buildings still used today as the center of Toulouse’s medical administration. Very few cars pass over the two bridges besides the ambulances, whose bright blue lights reflect off of the Garonne’s surface. The buildings are curved, so from my angle, it’s as though I’m looking through a fish eye lens. The dome to the right is undergoing some reconstruction, with the far left side covered in scaffolding. It was only until about 30 years ago that this was home to the maternity center in Toulouse.”

Saturday, the gears in my jetlagged brain started working again and I sent out 76 emails. Some to mentors I wanted to reconnect with and some to prospective farms I would like to visit. Initially, I found farm contacts on Yelp, Facebook, or by reading papers of researchers who visited farms. However I found an excellent collection where farms list their visitation times, types of dairy products, and contact info. I am not sure how active farmers are in responding to email envoys from this website, but I am optimistic the 20+ emails will yield some response. Additionally, I planned which days I would attend the two main Toulouse farmers markets, and contacted some cheese shops.

Sampling

On Sunday, I went to the Saint-Aubin Market just a few blocks from my studio. It was so wonderful! Dozens of vendors were set up around the church, from bread, to street food, to produce. There were a few dairy vendors, ranging from the one-person show with cheese in a hacked cooler on a trailer, to whole food truck-style stands with five people working it. To connect with local cheese and yogurt producers, I wrote a script in French that I was planning on showing to them in case we could not converse in English. It included questions about how long they fermented for, if they used starter, and information about their location and milk. I think I was a bit over-enthusiastic here, and did not end up having these conversations with the four producers I bought from that day. A couple were too busy, one waived off the conversation, and the last was packing up to leave when I caught them. This is completely understandable – I realize the information I’m asking for, with my broken French, goes above and beyond the sale of the item. I am still working out ways on how to best approach this, and hope my meeting with a local cheesemaker on Tuesday may help me clarify this.

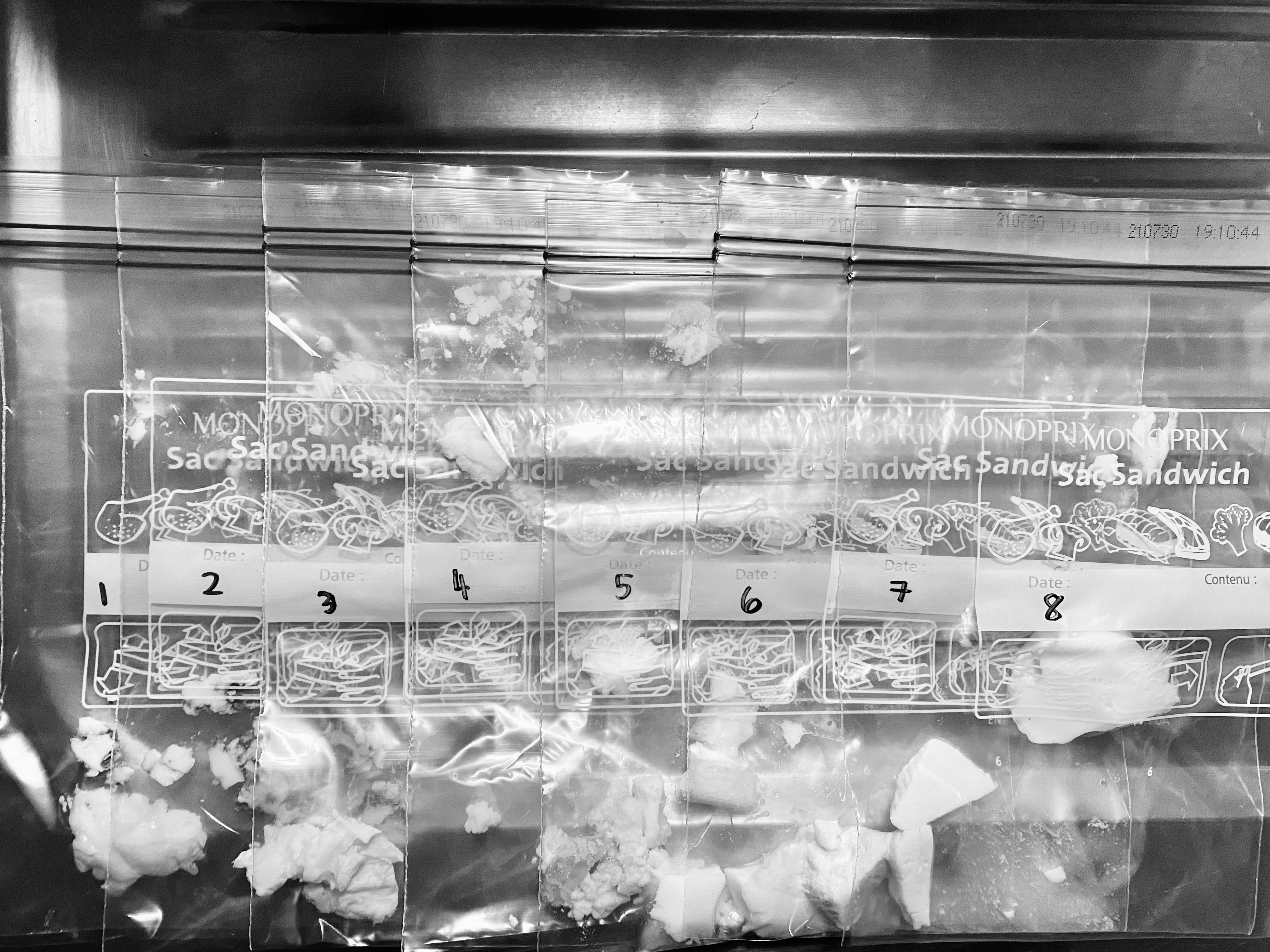

I sampled seven regional cheeses, six of which are made from raw (unpasteurized) milk, meaning they should have microbes beyond the starter. Ideally, I would be able to sequence the milk first, to see how the community changes over the course of fermentation. This may be a possibility in the future. Later that day, I sampled them as well, as I was packaging them to take to lab. They were all delicious! Although I am not a fan of blue cheese, the Roquefort was less heinous to me than other blue cheeses. This cheese is made in caves about an hour away from Toulouse. The fungus Penicillium roqueforti is responsible for the fascinating blue mold growth, and I should see this microbe loud and clear in the sequencing data. I will be keeping a log of all samples (and likely some eventual metadata visualizations) in the Sample Tracker tab.

That’s all for now, thanks for reading!

Liana Merk is a Watson fellow studying microbial diversity in fermented foods from around the world. She earned her undergraduate degree from Caltech in Bioengineering and will begin her PhD in Biophysics at Harvard in Fall 2022.