Thailand

Next stop: Thailand

Toward the end of my stay in Singapore, Japan’s borders were still closed. I wanted to remain in Asia in case Japan started letting in more entrances, because I had a great stay at a miso, soy sauce, and sake brewery lined up. There were a few countries that I could visit without quarantine, and Thailand was one of them. I cold emailed a few professors and one responded within an hour that he could host me for a research stay! Unfortunately, when I replied to get everything organized, I did not receive a reply from him. I reached back out to some of my mentors in the US, asking if anyone knew professors in Thailand who could host me on such short notice.

My last few days in Singapore, I met up with Professor Stanislav Presolski at Yale-National University Singapore, who put me in touch with a professor in Thailand. Professor Tao Uttamapinantwas interested in my project and invited me to join his lab in the remote region of Rayong, Thailand. After I set this research stay up, one of my mentors from the US replied, putting me in touch with Professor Monchaya Rattanaprasert at BIOTEC in Bangkok. I was excited to have the opportunity to work in two geographically distinct areas, as it would mean having access to a range of cultured and wild ferments.

Figure legend: My journey continues in Thailand. High res image needed

While setting up my research stays at both universities, I spent a week sightseeing and getting my scuba diving certificate in Phuket and Phi Phi island. I also started researching the different fermented foods that I wanted to sample during this time.

I flew back to Bangkok on March 15th, and Prof. Uttamapinant was kind enough to pick me up from the airport, a two hour drive from VISTEC, the research institute. I knew it would be remote, but I was shocked at the dichotomy presented by the institute. This region was designated a hub for innovation by the Thai government (EECI), and is undergoing massive development to create state of the art research facilities, very much in the middle of Thai forests! I was completely immersed in nature; there were even signs indicating elephant crossings.

Everyone I met was so friendly, and I felt fully incorporated into lab culture. I would often get to the lab, and someone would say, “Today I am going to this market to get food. You want to come?” So they would take me to these local markets and I would discover so many new fermented products with their help. It was incredible, and for the first time, I felt like I had partners with me in the sampling process. One day, they planned a trip to Chanthaburi, a riverfront village a bit south of Rayong. We’d often come across an older woman fermenting some produce in a plastic jug, and you could tell she’d been doing it for years. You could also tell from the potent smell that it had been sitting there fermenting for many months.

Across Thailand, fermentation is included in so many dishes, and fermented fish and meat are very popular. In this area, I was keen to collect samples of the most famous dish - som tum - a papaya salad with fish fermented for months or years. It includes liquid from fermented fish, called pla-ra, which is sometimes cooked (especially for tourists!), or consumed raw. I also took samples of the popular sausages hanging from the carts on the side of the road. I was hoping to capture how the pork intestinal microbes on the outside make their way into the meat inside during the casing process.

Unfortunately, I later discovered that it’s difficult to extract the bacterial DNA from the background of host DNA, so the sausage samples, for example, contain lots of pig DNA. There are kits available to selectively deplete host DNA, but I did not choose this kit at the start of my project.. My initial plan was to extract from only yogurt, which does not have high concentrations of host DNA. Once the plan shifted to adapt to COVID changes, I started collecting any type of ferment present and popular in the countries I was in, which includes those with high host DNA content. Because I want my samples to be extracted with the same method, I did not change kits at this point. We can imagine that amplification-based sequencing (like 16S and ITS) will be able to selectively amplify DNA from bacterial and yeast cells respectively. However, for metagenomics methods, where all DNA in a sample is read, having host DNA present will be an issue. Such are the challenges of beginning a project and not quite knowing what it will entail!

Before leaving VISTEC, I presented my project to a class of STEM high school students. This was planned to be in person, but there was a COVID case at the school – pandemic woes! After hearing their questions and seeing how interested they were about fermentation, I was even more motivated about my project. Sometimes after days or weeks of plans falling apart and difficulty in the field or in the lab, I can lose sight of the excitement. Giving this talk definitely re-energized me!

After two weeks in VISTEC, I spent a week at the BIOTEC Food Science department . While I was working in the Food Science department in Singapore as well, I did not have a dedicated mentor or professor. Here, Prof. Monchaya and Manadsareee, a research assistant in her lab, were giving me feedback and mentorship. While much of their research is focused on developing consistent and value-adding starter cultures for industrial applications, they were excited to help contribute to my study. Manadsaree was amazing. She organized several visits to different markets, including a road trip to Nakhon Ratchasima a few hours away. We went to a few different markets, had a local lunch in Pong Daeng, and visited a family-run Nham business (pork sausage wrapped in banana leaf) in Mueang. As in, we went into their garage and learned how they made Nham. It was an all-generational endeavor: grandparents cut and prepared the meat, parents wrapped the leaves, kids carried the full baskets of Nham ready to sell. It felt like I was peering into a tradition many decades in the making.

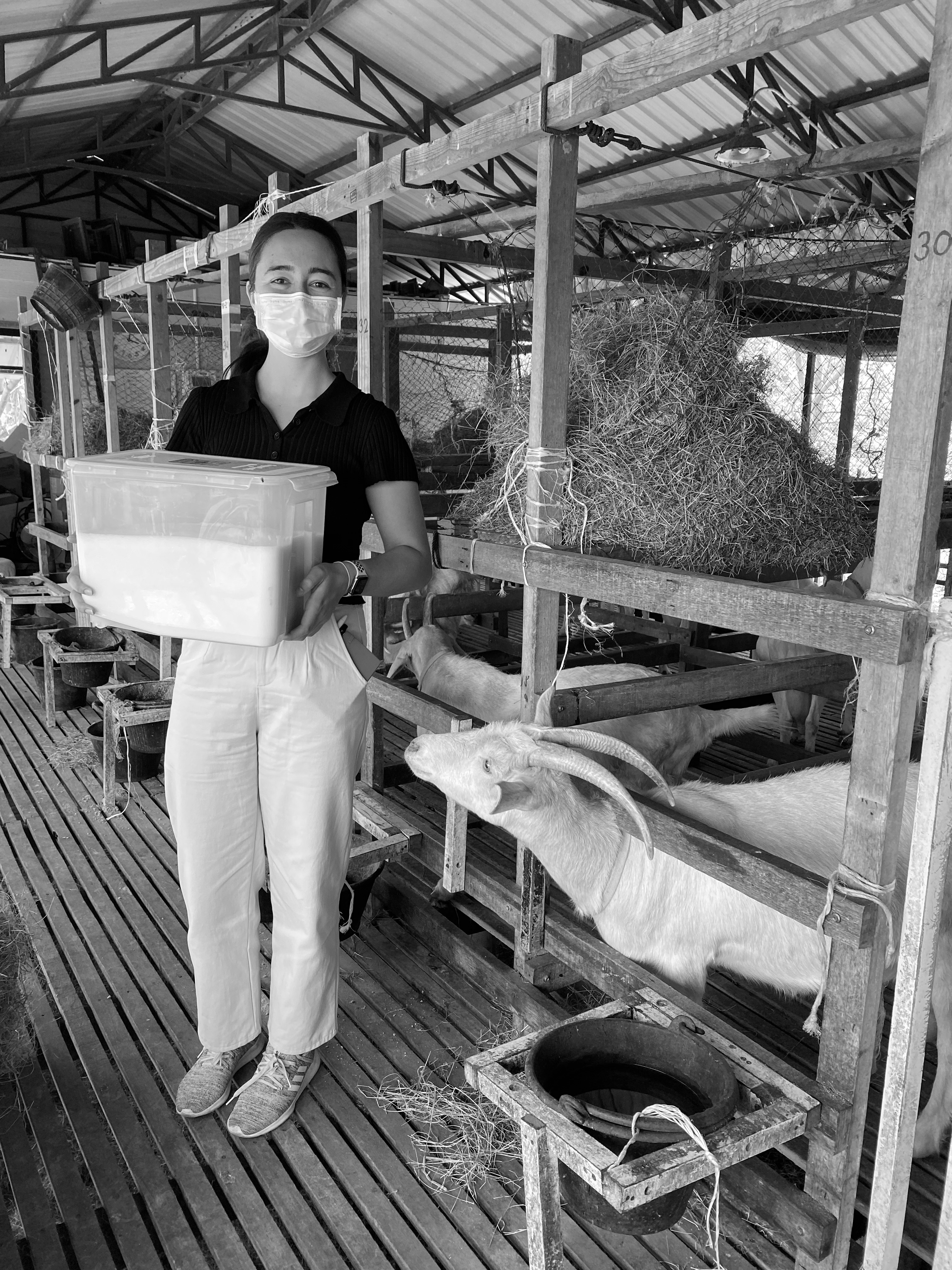

One of the farms we visited was a dairy farm in Nakhon Pathom. The owner is a trained veterinarian, so she is able to care for the goats and reduce the prevalence of a virus that runs rampant in most ruminant animals. Dairy farms are quite rare in Thailand since dairy products are not very popular. In fact, most of her customers are visitors or expats who miss the cheese from their home country. Dairy regulations tend to be adopted from European countries where dairy is more popular and thus more resources go into developing regulations.

The majority of the samples I took from the markets we visited near Bangkok were replicates of those in Rayong, which is excellent for a comparative study. I have around eight to ten samples of fermented whole fish, including a popular dish that involves stuffing the fish with rice and leaving it to ferment for several months. I also have two fermented rice samples that start as a sweet dessert on day one but become quite boozy after day 7. Other samples include fermented crab, jellyfish, and freshwater shrimp, as well as several different fruits and vegetables. One of the most unusual products I came across was a bright red home-brewed alcoholic drink of vodka, herbs, dried scorpion, snake, and centipede. I also made fermented spring onions in the lab and ran a time-course. It smelled a little garlicky, like the fermented durian from Singapore.

As I wrapped up my stay in Thailand, I reflected on how my view of fermented foods had changed since the inception of my project.

Fermentation is sometimes a way to try new cuisines. Borrowing sourdough starter from a friend to make fun bread designs. Leaving cabbage and radish with some salt to enjoy the kimchi that results. Sometimes, however, fermentation fulfills a need to preserve and persevere. It is selling bamboo shoots, naw-mai-dong, to put food on the table for your family. It is rolling a cart with fermented sausage, sai-krog-isan, down the street in 90F beating sun. It is teaching your kids to ferment fish, pla-som, with the hopes they will pass the traditions to their kids someday.

Fermentation has many paths forward. It impacts the way we think about stable microbial communities. It impacts health in ways that are currently being studied. It impacts the way we scale up the food industry. With all of the exploration and experimentation in fermented foods, we would be remiss to forget about the long standing traditions and knowledge that have brought us to where we are today.

Liana Merk is a Watson fellow studying microbial diversity in fermented foods from around the world. She earned her undergraduate degree from Caltech in Bioengineering and will begin her PhD in Biophysics at Harvard in Fall 2022.